Enter your name and email address to download this ebook.

Here Is Your Free Ebook:

The Source of Creation

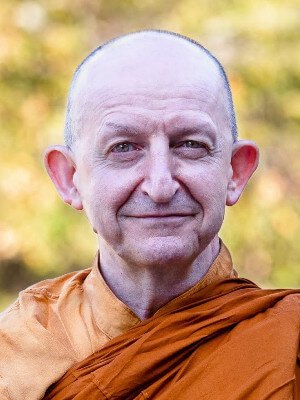

From a talk given during the Easter Retreat, Amaravati, 1991

As monastics, we are often asked where creativity fits into our way of life. The tone of a monastic environment is very simple. We aim at as simple a life as possible so people wonder where the creative instinct fits into all this. It is often difficult to understand why, for instance, music does not feature in our lives in the monastery when it seems to be so intrinsic to most other spiritual traditions of the world.

Since it is so often asked of us, naturally it is something that we contemplate and of course, as individuals, it is something that we are involved and concerned with, and consider in our own way. Often the assumption is that, since the monastic life represents the epitome of spiritual life, we have to strangle the creative impulse or the capacities that we have, our talents, inclinations and creative abilities. All of that has to be hidden away or discarded, and looked on as distractions, unnecessary for Enlightenment.

This is not really a healthy approach. Many of the people in the Sangha have creative backgrounds and are very artistic. The other day I was talking to an anagarika who had been helping in the Italian vihara for the last few months. Though there were only 4 or 5 people in the vihara, there was a former anagarika living locally who was a jazz pianist and singer; the anagarika who visited us used to play the saxophone; Ajahn Thanavaro used to be a drummer and Ven.

Anigho was the lead guitarist in a well-known band in New Zealand. These facts came to the attention of the members of the Sangha here in England, who politely asked if the artistes had ever got together. The reply was, “No, no! And if we did, I never told you so!!” So it is not as though the people who are attracted to living a monastic life are bereft of the inclination in these directions.

This place is stuffed full of poets, artists and musicians of one sort or another and you might have noticed that, generally, we are not a repressed bunch of people. So how does it all fit together?

The Buddha was often criticized in his own time as a life negator. There is something within us that is very strongly affirmative towards life and our existence as human beings. That “life affirmation” is highly praised and given a lot of energy and support in our society. In our own time, as in the time of the Buddha, to be enthusiastic about life, to take one’s life in both hands and really make something of it is highly praised, and we celebrate someone who has “done something with their life.” And so the Buddha’s whole approach towards spirituality – promoting renunciation, celibacy, simplicity, non-accumulation and so forth, has attracted much criticism. People used to call him an annihilationist, someone who was denying the spirit of life and the spirit of all that was good and beautiful in the world; someone who was a big downer on life, who held a nihilist philosophy – “it’s all pain,” “it’s all a dreadful mistake,” “it shouldn’t have happened in the first place.” “You have to minimize your life, grit your teeth and wait until it’s all over, and the sooner the better!”

It was felt that the Buddha really held that kind of a view. He was questioned on it and he once replied that his Teaching did tend more in the direction of the nihilist than the affirmative, “My Teaching is much more in the direction of desirelessness, of coolness rather than in the direction of desire, of getting, of possessing, of accumulating.”9 Yet it would be incorrect to call the Buddha-Dhamma a nihilist philosophy; it is not life-negating.

The Buddha said that because of the way that we are conditioned as human beings, we tend to drift into the two extremes of, on the one hand, affirmation – affirming and investing in conditioned existence and seeing the beauties, delights and good things that life possesses in terms of what can be achieved or derived by conditioned existence – or, on the other hand, criticizing the conditioned world as a dreadful mess, a mistake which one wants to get away from. The Buddha pointed out that these are two extreme positions that we fall into and are points of view on life that do not actually respect the true nature of things, because they are bound up with the view of self, the view of the absolute reality of the material world, and of time.

This is not seeing things in a clear, true way. What the Buddha was always pointing to was transcendence of the conditioned sensory world, of selfhood, and the illusion of separateness. When we sit in meditation and look into the nature of our own minds, we can see how much the mind will grasp at anything.

Depending on our character, sometimes it will grasp at positivity – affirming things to get interested in and excited about, or it will grasp at negative aspects that we don’t want to bother about or that we want to get rid of. But any kind of holding on or pushing away, however subtle, affirms the sense of self. Even if the impulse is destructive or nihilist, we still operate from the view there is something here which is “me” or “mine,” which “I” want to get rid of and not experience, it’s an intrusion upon “me,” a corruption in “me,” and I don’t want to bother with it. I want to get rid of it.

Sometimes, when the mind has a really perverse streak we can even bring pain upon ourselves; we can actually know that something is wrong, is going to bring pain to us or to those around us – but we go ahead and do it anyway. “I know it is wrong, I know I am going to get into trouble; I know it is going to hurt; I know I am going to get criticized for it, but I am going to do it anyway!” – the “spitting at God” impulse! – “And I don’t care if you are the Creator of the Universe!”

–

If you liked this free mindfulness ebook and would like to make a direct financial contribution to this teacher, please contact them here: http://www.amaravati.org/speakers/ajahn-amaro/

–

Material on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License

Enter your name and email address to download this ebook.

More from: Ajahn Amaro