Enter your name and email address to download this ebook.

Here Is Your Free Ebook:

Ultimate and Conventional Reality

The meeting of spiritual traditions, including that of Theravaμda wisdom teachings and Dzogchen, two great expressions of the Buddha-Dharma, is one of the major beneficial aspects of life in these times.

The technological revolution makes the ability to travel, to communicate, and to study across traditions very simple. Most of the world’s great spiritual texts are online, and a steady stream of conferences and retreats brings meditators, scholars, and spiritual masters together to practice and to openly discuss their lineages, insights, and knowledge.

The breakdown of separate spiritual encampments that is occurring nowadays is both remarkable and unprecedented. For the first time, we can enjoy a broad view of all traditions and see where they merge as well as where they collide.

I was reminded of this marvelous confluence of traditions the other evening, just as this retreat began. Shortly before 7:00 p.m., I was sitting in my room. In the midst of the quiet and calm, I heard a loud thumping noise coming from outside.

We were doing a lot of earth moving at the monastery at the time, so the noise made me think that maybe some heavy equipment was being brought in to help us along. I imagined large yellow mechanical devices rolling up the road to the retreat center.

But then I heard what I thought was a huge engine making bang! bang! bang! noises. Eventually that stopped and was replaced by a loud trumpeting sound. I thought, “Maybe it’s one of those Dzogchen parties, and the powers that be think the bhikkhus shouldn’t be invited.”

But then I realized that that kind of party, the Dharma feast, is at the end rather than the beginning of the retreats. So I continued to wonder, “What could this mean? What is this loud ruckus?” I figured I’d find out at some point.

It slowly dawned on me that it was the beginning of the Jewish New Year, and I recollected that one Jewish tradition had something to do with blowing horns and banging drums.

Then I remembered that in the Tibetan tradition it is said that when the Buddha was invited to teach by the brahma gods, the gods came along with a conch horn and a Dharma wheel to make their request.

I thought, “Maybe this isn’t a Jewish tradition after all. Perhaps it’s the brahma gods coming down with their conch horns and Dharma wheels to invite the teachings.”

In fact, the sounds I heard were part of the Jewish New Year’s ritual, and it was Wes Nisker who was blowing the shofar, the ram’s horn trumpet. I later learned that the harsh blast of the shofar symbolizes the call to awaken out of unconsciousness.

Hearing the shofar serves as a reminder of our higher calling, of our true purpose—to awaken and be free. This is a wonderful time to be alive and to be present for such camaraderie as this between different spiritual traditions, both within the Buddhist world and between religions.

These inter-connections encourage us to see beyond the externals of a spiritual tradition, yet they also illuminate the conundrum that we live with.

On the one hand, we have the verbal teachings, traditions, and structures that enable the insights and values to be carried through time and space across the planet.

On the other hand, those same structures can become the things that inhibit and obstruct the very truths they are trying to convey.

We are extremely lucky that Buddhism is so new in the West. Many people have reflected on the notion that “these are the good ol’ days.” In 100 years, we will have a Buddhist president, there will be big grants from philanthropists, and Buddhism will have become institutionalized.

People will become Buddhist to climb the social ladder, and the glory days will all be over. So we are lucky to be practicing before Buddhism becomes part of the social norm.

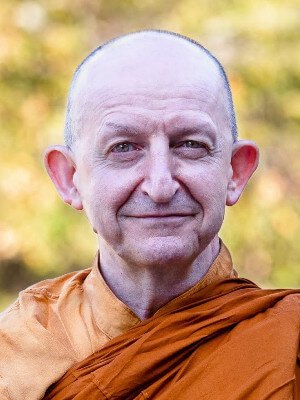

To be a Buddhist at this point in time is to be out on the fringes. After all, in conventional terms, there is very little social value in being a Buddhist. One of the biggest drawbacks I find to being a monk in Asia is the automatic value that people give us because we have shaved heads and robes.

People in Asia think we are something special, while in the West they think we are just kooks. We get shouted at in the street with all kind of remarks. In England, it’s usually something like, “Skinhead!” “Hari Krishna!” or “‘Allo ’Ari!”

This coming together of different spiritual expressions, in which there’s both an understanding of religious forms and a commitment to them, is indeed precious. But there’s always the challenge within this supportive context to see beyond that—to use the form and, at the same time, to see through it. We need to be able to pick up the convention and use it merely as that.

On the inside, we need to be completely free, without boundaries; we need to let go of everything. On the outside, we need to be really strict and proper, to follow the routine and do everything according to the rules. My own experience is that it takes a while to appreciate the true meaning of this.

The Search for Freedom

Probably like many people, I wrestled at length with the question of freedom in my teens and early twenties. I was a late flower child, having been born in 1956. I just caught the tail end of the good stuff.

Through much of my early years, I worshipped the ideal of freedom and longed for the true experience of it. Rather than becoming a bomb-throwing anarchist, though, I became more of a flower-waving, philosophical anarchist.

Nevertheless, I took this aspiration to freedom very seriously. And I had a profound intuition that freedom is possible—that there is this potential we have as human beings to be totally free, and that there is something utterly pure, uninhibited, and uninhabitable within us.

My experience, however, was one of colliding with endless restrictions and frustrations. First it was getting away from my parents; then it was the law; and then it was not having enough money. I thought that this or that was standing in my way, and if only it wasn’t there, I would be free.

If you liked this free mindfulness ebook and would like to make a direct financial contribution to this teacher, please contact them here: http://www.amaravati.org/speakers/ajahn-amaro/

*** Material on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License

Enter your name and email address to download this ebook.

More from: Ajahn Amaro